Castles on the Rhine aren't there accidentally. The Rhine

is a big river, and ever since boats were invented, this river has been

Europe's most valuable means of commerce.

For millennial bends in the river provided ideal spots for bullies to

build castles overlooking bends and tributaries to extract fees from merchants

needing to go upstream and down.

Toledo was born with that idea in mind; but Spanish

rivers are fewer and don't command much commerce. Still, Toledo is imposing, looming over the

plain to the north like a sentinel. A

military couldn't do much about Spain without controlling this city built on a

huge rock. It has the fewest level

streets of any European city.

I didn't have an urge to dominate the Castile region, but

I did want to spend time in a city that

has a cathedral that resolved its unfinished dome problem by having angels

flying around the hole. I wanted also to

see El Greco's home. He couldn't marry the love of his life because, since she

was a Jew, if he married her, his son would be ostracized. (You figure that one

out).

I didn't have an urge to dominate the Castile region, but

I did want to spend time in a city that

has a cathedral that resolved its unfinished dome problem by having angels

flying around the hole. I wanted also to

see El Greco's home. He couldn't marry the love of his life because, since she

was a Jew, if he married her, his son would be ostracized. (You figure that one

out).

Actually, I went to Toledo because I'd been told that it

is the number one place in the world to see how Damascene is made. The number one shop is just north of the monster

rock that is the city.

Damascene

refers to Damascus, the probable city of the technique's origin. The decorated steel figures appeared when

Turkey, Syria, and the Caliphs of the Tigris/Euphrates were beating up on

everyone in general and had established a lock on southern Spain. The world's

best steel then was Persian made. The Caliphates tossed in stuff like Algebra,

medicine, cotton, and were pretty good at building palaces and mosques. They

became incredibly good at decorating things, including armor and plaster. Decorating

their horse trappings and armor with delicate designs of gold on steel was the

ultimate in their art.

Damascene

refers to Damascus, the probable city of the technique's origin. The decorated steel figures appeared when

Turkey, Syria, and the Caliphs of the Tigris/Euphrates were beating up on

everyone in general and had established a lock on southern Spain. The world's

best steel then was Persian made. The Caliphates tossed in stuff like Algebra,

medicine, cotton, and were pretty good at building palaces and mosques. They

became incredibly good at decorating things, including armor and plaster. Decorating

their horse trappings and armor with delicate designs of gold on steel was the

ultimate in their art.

When Isabella and Fernando rooted out the last of the

Moors (who were mostly north African), some Spaniards had mastered this mostly secret

art of welding steel to gold.

If it had been the high season, I might have been out of

luck to learn much; but as soon as I showed interest in the torches, the

supervisor of the shop I examined gave me a tour that lasted all afternoon. The

lead welder explained why the torches

were of varying sizes, how they fused the steel and gold, and how the black is

applied. I was allowed to meander everywhere, which was about the size of two

tennis courts. As you might expect, not the tiniest amount of gold ever

hit the floor, or disappeared. A little steel

might be burned away, but very little of that either.

Once I commented on an interesting steel design high on a

wall. The foreman instantly went ballistic.

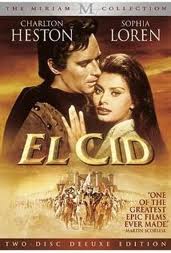

"EL CID!!!" he yelled.

When he eventually cooled off enough to speak at a pace I

could track, he led me to understand that a movie company (American) had

produced the film "El Cid" on location near Toledo and contracted for

all sorts of welding and weaponry and other props useful in the film. But they

had not been very forthcoming with cash when due.

"Hollywood!" my tutor finally grumbled, drawing

a finger across his throat. When he eventually stopped sputtering, he murmured something

that was probably just as well I couldn't translate.

At last he smiled. He pointed toward a large sign outside

the shop that told visitors there was a forty percent discount on Damascene

that day.

“For the buses,” he said. “Means nothing." Then he

added, "Don't buy when the buses are here. When there is just you, then

buy. Not forty percent... Eighty percent.”

I still have the bolo I'd watched him make from a blob of

gold and a piece of steel. AND I got it

at eighty per cent off some price he invented because "the bus

people" were not shopping.

.jpg)